Tzafrir speaks of horror and hope as daughter of two holocaust survivors

Tzafrir’s talk began with an introduction to her family. “Growing up in the home of two holocaust survivors who went through the death camps and survived, meant for me a feeling of loss and sadness. It was something you could not escape,” Tzafrir said. This collage features different images of her family, including a picture of her mother in 1946, a picture of of her parents when they got married in 1949, a picture of Tzafrir and her sister in the 1970s, and a recent picture of her father.

February 24, 2016

Iris Tzafrir spoke about both the horror and hope experienced as the daughter of two holocaust survivors during tutorial Feb. 23 in Driscoll Family Commons. Tzafrir’s well-attended talk arranged by the Upper School Council relayed her family’s history with the holocaust, leading to unexpected and optimistic turn of events that resulted from her eventual confrontation of her parents’ past.

“Growing up in the home of two holocaust survivors who went through the death camps and survived, meant for me a feeling of loss and sadness. It was something you could not escape,” Tzafrir said.

Tzafrir’s father was originally from Poland and her mother was originally from Hungary. Both lost their families in the holocaust, were forced into Auschwitz and eventually immigrated separately to Israel, where Tzafrir grew up.

“When I was young, I didn’t want to learn about my family’s history. It was just too painful for me,” Tzafrir said.

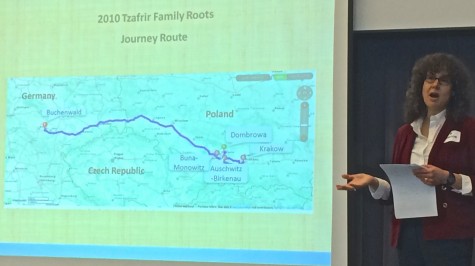

However, in 2010, Tzafrir, her father and her three brothers went on a journey retracing her father’s the death march from Buna-Monowitz to Buchenwald, Germany undertaken at the end of 1944.

Tzafrir’s father wanted to show his children places of importance to him before and during the holocaust. In 2010, her father and her siblings traveled from from Buna-Monowitz to Buchenwald, Germany, along the route of her father’s death march.

Although Tzafrir described feeling physically sick before the trip, she explained that, ultimately, it was a healing experience. Now interested in family history, Tzafrir searched for her father’s missing family and found that her father’s sister, who had been separated from him during the holocaust, been living in Israel. Although her father and his sister had lived within two hundred miles of each other for decades, neither had known of the other in their lifetime.

This trip changed how she thought about the holocaust, her attitude toward it, and how she told the story of her family’s history.

“The Shoah [Hebrew for Holocaust] is something that has effect for generations to come and all over the world,” Tzafrir said.

Now, Tzafrir speaks regularly at school, churches, and community centers. Her family was featured in the Minneapolis Star Tribune.