Smartphones make for useful learning tools

October 26, 2014

Smartphones prove to be as useful to studying as other forms such as through a computer or from a book.

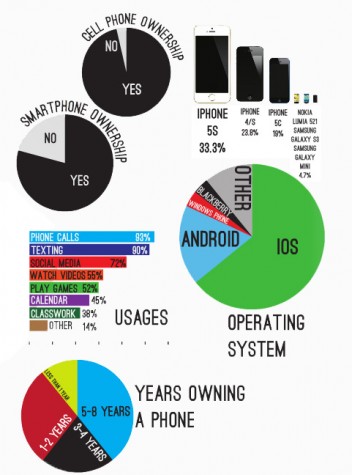

They’re everywhere–bathrooms, hallways, bedrooms, subways, stadiums, kitchens, backpacks, purses, pockets and maybe even…classrooms? Slowly, they’ve changed people’s postures and altered the way they communicate forever. They can reach each other an instant from across the globe. And, they know everything there is to know to boot (and maybe even where you live). “So, what are these omnipresent objects, anyway?” one might ask. Smartphones, of course. These amazing devices have now placed the entire internet and more in the palms of the hands of 79% of SPA students. Since the Personal Digital Assistant (PDA), smartphones have evolved into what is now the sleek beast that is iPhone 6 with its new, A8 processor (the latest smartphone to come out this year). In fact, they have gotten so powerful that they may even begin to replace PCs. So, as laptops have found a place in a school setting, how might smartphones, once the bane of any teacher, be a tool for learning?

“It’s a very natural way to collect information,” Upper School history teacher Ryan Oto said, “as a resource, it provides accessibility.” Smartphones turn on easily and users are one tap away from an internet browser. In fact, the average 4G LTE smartphone can now reach speeds that are faster than or equivalent to a home broadband network.

With such a powerful tool, discussions no longer have to go on fact arguing tangents. Upper School English teacher Matthew Hoven “sometimes assign[s] students to fact-check during discussions.” Unfortunately, “people [could] get so caught up in fact-checking that it kills the rhythm of the discussion,” Hoven said.

Many SPA students own smartphones. About 38% of students use those smartphones for classwork.

Oto has used smartphones and social media for lessons in the past. “I made [my students] all make Twitter accounts and tweet like a politician from the Colonial Era and they had to tag me,” Oto said. In a way, he “tricked [students] into learning.”

Upper School science teacher Ned Heckman often lets students use smartphones as calculators or to take pictures of board notes. Even though he hasn’t used them for teaching, he would like to learn how. For now though, he’s confident that his classes are “interesting enough that [he doesn’t] have to use [smartphones] just yet.”

Smartphones provide quick and easy access to internet, helping students when they’re in a pinch. “I lost my computer…[and] I had all this homework on my Google Drive. So, instead what I did was on my phone…I downloaded the Google Drive app and I did all of my homework on that app and it worked out perfectly fine. It was a life saver,” sophomore Muneil Rizvi said.

“It’s pretty helpful because I can just use it on the go, I don’t have to lug a book around with me. I have [an app] for SAT vocab which I probably find the most helpful because it makes it easy to study,” junior Christine Lam said, “I find it’s easier to [use apps] because they have games on them and it’s a pretty interactive way to study. A downside would be that they kind of cost a lot, but it’s still good because I don’t want to bring around a huge thing of 500 flashcards with me.” Smartphones are a great way to keep study materials in one place and provide mobility.

Likewise, for sophomore Neeti Kulkarni, smartphones are a convenient way to study. “If I’m in the car or somewhere where I don’t have internet connection, I can quickly look up a definition or a formula that I need for the next day if I’m working. It’s really helpful because I have to go around to a lot of different places,” Kulkarni said.

But would learning move in a direction where paper notes and printed homework are replaced with more efficient methods such as turning in homework digitally or typing and digitally recording notes verbatim? The results in a study by two psychological scientists, Pam Mueller of Princeton and Daniel Oppenheimer of UCLA, say otherwise. Instead, they suggest that “longhand notes not only lead to higher quality learning in the first place; they are also a superior strategy for storing new learning for later study. Or, quite possibly, these two effects interact for greater academic performance overall.”

“Obviously, [smartphones] are distractions,” Oto said, “thinking they are not would be naïve.”

With even faster ways to multitask on smartphones, it is easy to switch between class appropriate applications of a cell phone and not. “Allowing kids unrestricted access to phones could lead them to start texting during class,” Hoven said.

Still, using smartphones in a class setting entails some difficulty. “Not everyone has a smartphone, which is a big issue,” Oto said, maintaining that, if a student does not own one, smartphones are “still a barrier to accessibility.” To counter this, Oto “would do classes where [he]’d put the groups all together with kids with smartphones.” Though he hasn’t used smartphones in a lesson this year yet, Oto hopes that he will in the future.

Evidently, smartphones are useful tools for learning, but their place in the classroom is yet to be determined.