Open YouTube. Type in the two words. You know the ones. Watch the videos appear, row after row: nowhere to go…great places erased…what our cities are missing. Do the same on TikTok, Instagram, any platform of your choice. The world is opening its eyes to an integral but vanishing element of culture. It’s ironic, then, that the majority of discussion is online, given the two words in question: third places.

Coined by sociologist Ray Oldenburg in his 1980 novel “The Great Good Place”, the term “third place” refers to the places that facilitate social interaction outside of the home, the “first place” and school, the “second place”. At these primarily social locations, one encounters a mix of “regulars” and new connections, which encourages relationship building. Third places have historically included parks, libraries, diners, automats, cinemas, bowling halls, hair salons, community centers, churches, and cafes.

Third places are inseparable from youth culture. Which age demographic was spending the most time out and about, looking to hang with friends or dates? One only needs to watch a film or show twenty years old to notice. Third places have been an integral aspect of the teenage social sphere ever since teenagers have been going out independently — in other words, essentially the whole of the last century, and well before Oldenburg coined the term. However, despite recent discourse online re-popularizing the term, the third place is rapidly disappearing.

There are several prominent factors in the decline of the third place as it was known in the twentieth century. Third places — especially those revolving around food — are often centered in cities. Progression of the twenty-first century occurred concurrently with the rise of suburbia, and as populations spread outward from cities, the necessity of large-scale, quick-service dining that automats and similar establishments provided declined. This movement eliminated the diversity of interaction born out of necessity — at automats, individuals of different races, different classes and even different languages sat and ate side by side. Automats, however, worked on the economics of scale, and the introduction of highways and rise in car culture eliminated the market. Both automats and the diners that emerged later were eclipsed by space-saving, widely dispersed chain restaurants.

Another significant factor in the inaccessibility of food-centered third places today is rising prices. Before 1950, an automat would sell a cup of coffee for $0.05. Accounting for inflation, that’s $0.64 today. At Starbucks, the price for an average-sized black coffee is $2.75. Cafes are self-selecting: only people of a certain economic strata can afford to frequent them daily. And even among those individuals, the prices are so absurdly high that it’s more difficult to sustain regulars at the same rate diners or automats could.

And then, of course, there’s the elephant in the room: digital spaces. Throughout the twentieth century, social life outside of the home declined as leisure became more privatized. Take, for example, watching a movie. Almost as soon as the word teenager came into popular usage in the 1940s, teenagers began to be viewed as a group with spending power, and therefore needed to be marketed to accordingly. One aspect of this cultural shift was the genesis of the teen movie. Beginning in the 1950s, Hollywood catered to young audiences with films like Blackboard Jungle and Rebel Without A Cause, which presented common experiences such as rebellion, alienation and angst on the big screen. As a result, youth, money-allowing, frequented the cinema. In the ’70s and ’80s, as television became increasingly accessible at home, families began to sit and watch TV together inside the house. And with the advent of streaming services, cinema attendance has dropped even lower: In 2022, 61% of Americans did not see any films in theaters, compared to 2007’s 32%.

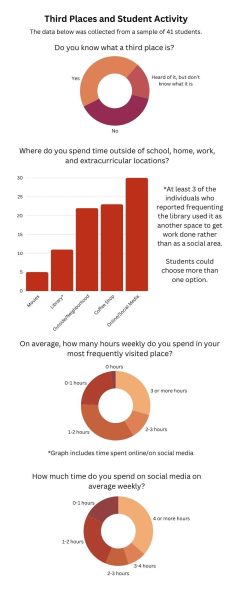

A similar pattern has followed social media usage, which has corresponded with the proliferation of mobile phones. Apps like Snapchat, Instagram, and TikTok cater to tween and teen audiences, and, as with anything cyclical, the more a group known for being on a platform is advertised that platform, the larger the group will get. As a result, youth spaces have largely moved online, and fewer teens frequent local businesses or recreational areas. Video killed the radio star; suburbia and social media killed public socialization.

Unsurprisingly, the decline in third places has coincided with the decline of youth culture overall. Consider the 2000s — the 2010s, even — and compare that with today. Where did all the Abercrombie and Fitches go? Seventeen and Smash Hits magazines? When did subcultures die and become the edgeless, inordinately consumerist aesthetics of TikTok?

This is partly due to marketing. With youth moving online into spaces inhabited by adults, the marketing has shifted — now, youth are sold adult products and lifestyles (see: the dreaded epidemic of Sephora tweens). As teens move online, so do their lifestyles. Notice the lack of the mall scene from the 2003 film in 2024’s Mean Girls? It’s not just because the script was rewritten for the Broadway stage. Malls are no longer relevant in the compendium of teen hangout locales; in Mean Girls, as in the real world, that vacant space is filled by phones. Why go to a mall when you could order online?

Given this decline, it is essential to reestablish the merit of third places. Spending time in third places is an excellent way to make new friends, take time away from school work and home life, and build relationships with the local community. They can additionally be exceptionally freeing from the expectations of productivity that follow individuals outside educational or work spaces, a phenomenon augmented in the post-pandemic era.

Third places are exceptionally important for students at St. Paul Academy. SPA exists within a social bubble — every day, students are exposed to, more or less, the same kind of people, individuals who possess approximately the same socioeconomic status and exist at the same end of the political spectrum. Now that the necessity of mingling is gone, we, as all Americans are wont to do, have settled back into the comfortable, well-worn habit of prioritizing things that provide us convenience rather than things that will help our mental and social well-being.

When it comes down to it, third places aren’t really about the place. They’re about the people and the interactions you have. And in a world oversaturated by online noise in which we’re disincentivized to go outside, the connections you make truly matter. So do yourself a favor and go find one. You won’t regret it.

Jared • Feb 28, 2024 at 3:40 pm

Here in Indiana, I have not heard of third places. But, as I think of my teen years, there were those spots where we would gather. Of all the places, we would sit in the parking lot of the local John Deere dealership. It was across the street from our Barney Fife police station that didn’t even have a jail. The cops would come up and talk with us, and the owner of the lot did not care we were there, so long as we didn’t leave trash behind. He even put a trash can out for us. We would spend hours in that “third place” talking, as cell phones came in a bag, needed to be plugged into the cigarette lighter, and were not prolific. It is sad that third places have disappeared for so many and the digital world online is now where teens spend their time. This is a great and thought-provoking article!