INFORMATION: 270ToWin Census (Annika Kim)

First established in the second article of the U.S. Constitution, the Electoral College is the system of how the U.S. elects its president. Unequal representation, historical racism, and discrimination have long been striking flaws in this process, but to understand the complexities of this system, one must first know how it works.

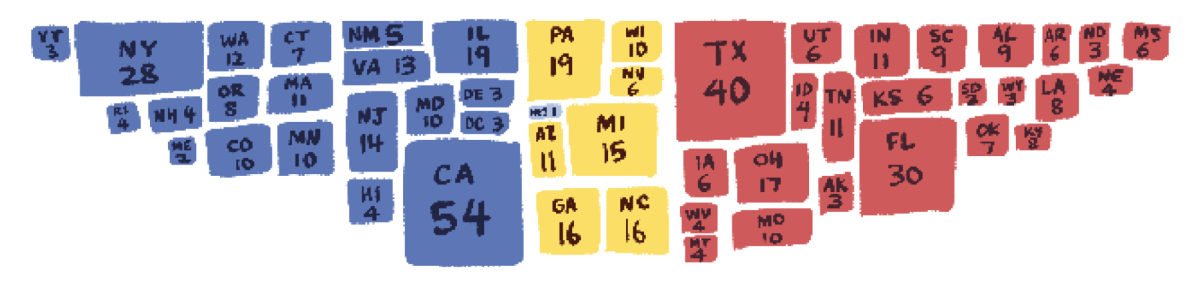

Under the Electoral College, each state is delegated a certain number of electors depending on its population. Districts, like Washington D.C., get three, and territories, like Puerto Rico, do not qualify for electoral representation. In total, there are 538 electors, and a presidential candidate needs a majority of 270 to win.

Elector candidates are chosen from a slate of nominees provided by each political party. The public in each state will then be allowed to vote for their electors during the general election on the ballot.

Once an elector has been selected, they will cast their vote with the presidential candidate who has won their state’s popular vote. Also called the Winner-Take-All system, if a candidate wins the majority in a state, they win all of the state’s electoral votes. The Winner-Take-All system holds for all 50 states, with the exception of Nebraska and Maine, which distribute their electoral votes based on the percentages of votes for the two candidates, meaning their electoral votes can be split between two candidates.

“I honestly think that [splitting state electoral votes] might actually be better … people’s votes count more because you’re not just putting them in a large pool and saying [their] vote is overshadowed by everyone else’s,” junior Shefali Meagher said.

If an elector votes for a candidate they did not pledge to vote for, meaning not their state’s majority or not the split ratio in Nebraska and Maine, otherwise known as “faithless electors,” they could face fines or disqualification and substitution depending on their state’s laws. If no candidate wins a majority of the electoral votes, then the decision goes to the House of Representatives, which has only happened twice in 1800 and 1824.

The primary complaint with the Electoral College is that voters don’t actually vote for the president; they only determine how their state’s electors are voting. Junior Desmond Rubenstein points out an example: “Minnesota, in reality, might be more 60:40 (percentage split), but we often vote completely blue in the Electoral College.”

Leaving the electoral decision to a select few often conflicts with the voices and opinions of the wider population. For example, there have been a few instances where a candidate has won the Electoral College but not the popular vote, namely in the 2016 presidential election.

Historically, the Founding Fathers designed this election system to take the decision-making power away from the “common people,” or, in their eyes, civilians who were not educated enough to decide who would hold the presidential office.

Later on, this system was used to exclude many minorities, especially people of color, who were not given the right to vote until much later. These minorities still counted towards the state population, determining the number of electors, but without the right to vote, they individually could not impact the election outcome.

The National Archives found that over 700 proposals to eliminate the Electoral College have been submitted since its inception. Unfortunately, even with all the discourse around the electoral system, no substantial change can happen without passing an amendment because the system is outlined in the Constitution.

Rubenstein proposes using the popular vote in place of the current procedure. “[The electoral process] would need to be probably still be based around population … not be based on a Winner-Takes-All system, if it would be truly democratic. Currently, the popular vote is probably the closest you can get,” he said.

Despite all of the controversy around the Electoral College, some students see the benefits of sticking with the system. “The only time it seems bad is when you don’t win the popular vote but win the Electoral College, just because [that means] most people in the country don’t even like you. But I just think it’s a good idea because the country is supposed to be united in a way where everyone can compromise to follow certain things,” Meagher said.

As this year’s election cycle concludes, the legacy of past controversial voting decisions looms large.

Senior Veronica Dixon voted for the first time on Nov. 5.

“Voting is important to me … I’m excited to participate in the system but I’m not excited about the system I am participating in,” Dixon said.