On Sept. 30, in a stunning show of bipartisanship, a nationwide crisis was averted. Millions of federal workers across the country would have been furloughed or forced to work without pay indefinitely due to a government shutdown, and this would have been the 22nd shutdown in the last 50 years.

“Any institution needs money to run itself because it has expenditures. The federal government … is no different,” upper school history teacher Aaron Shulow explained. “Congress has to work together to determine how much it can spend and how much it can borrow.” When Congress is unable to come to an agreement, the government will shut down.

More specifically, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, in order for government programs and agencies to function, Congress must pass funding appropriations–laws that “[provide] an agency with budget authority,” according to the US House of Representatives Glossary. There are 12 appropriations bills that must be enacted annually. A shutdown occurs when Congress is unable to pass the necessary spending legislation to keep the government operating. As of a week before the end of the fiscal year (beginning on Oct. 1), Congress had yet to pass any of the appropriations, and another shutdown was anticipated.

This would mean that “all non-essential services of the federal government would not open and those federal workers would not get their salaries; in many cases they’d be furloughed or temporarily laid off,” said Shulow.

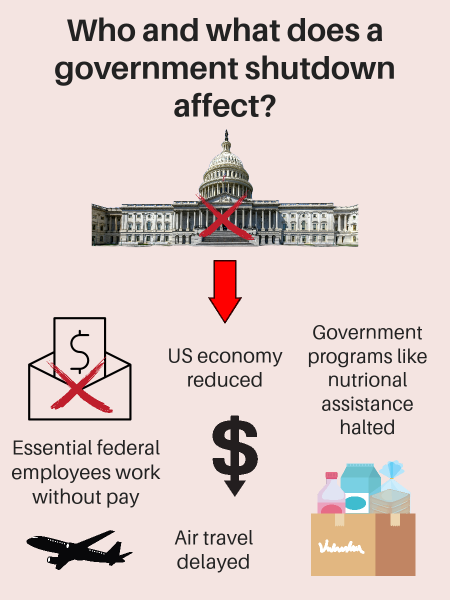

The American Federation of Government Employees estimated that a shutdown would impact four million military and civilian workers, including 2.2 million federal employees. “Essential” federal employees in professions such as law enforcement and military service would continue to work but without pay, according to the White House’s statement on the shutdown on Sept. 20. Others would be furloughed–temporarily suspended from work, with no payments–but thanks to a 2019 law, those employees would be compensated after the shutdown ended.

Even for non-federal employees, a government shutdown would cause disruptions. The White House’s statement noted that government programs such as the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children–which provides nutrition assistance for about seven million people–would lack the funding to continue during a shutdown. In addition, air travel would be delayed throughout the country as many employees would be forced to work without pay. Clinical trials and new grants would also be delayed, and national parks would close. Overall, the country would be more vulnerable during a shutdown, with few or no emergency funds in case of natural disasters or public health crises.

“The fact that this could have happened shows how much power the government has, how much power Congress has, and if [the government] shut down … society would just fall apart,” said senior Nora Shaughnessy.

The longest government shutdown to date lasted 34 days, from late 2018 to early 2019, under the Trump administration, and in that time, effects were seen across the country. The Congressional Budget Office detailed in its 2019 report on the partial shutdown that the shutdown “delayed approximately $18 billion in federal discretionary spending for compensation and purchases of goods and services and suspended some federal services.” In addition, the report noted reductions in the real gross domestic product (GDP) during the fourth quarter of 2018 and the first quarter of 2019 (in which the shutdown occurred). Overall, they found “more significant effects on individual businesses and workers,” specifically the federal workers who were not paid during the shutdown.

Tensions have flared between House Republicans and Democrats unwilling to compromise on spending; Democrats advocated for aid for Ukraine while Republicans backed border security.

“It would be a very disappointing thing to have all that havoc wreaked based on people not settling their own personal differences,” said senior Ford Reedy.

Similarly, in the days leading up to the deadline, the White House referred to the situation as a “Republican shutdown” in its briefing.

Shulow said of this stark political polarization: “There is less willingness to collaborate and in some ways people are incentivized to not work together because they get more attention if they are more combative than collaborative.”

Despite these divisions, late on Sept. 30 (hours before the deadline), President Biden signed a temporary funding bill to avoid a shutdown and all of its drastic effects. The bill was supported by Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy, to the dismay of some of his Republican colleagues, but it overwhelmingly passed the House and Senate (335-91 and 88-9, respectively). Despite this temporary relief, the bill only funds the government until Nov. 17, and after that, the future is uncertain.