Hodges promotes project, uncovers history of racial covenants

Mapping Prejudice nuances the legacy of housing restrictions in Minneapolis

October 25, 2018

Students, who uncover the racial disparities embedded into world history, can now contribute to a project that reveals racist deed covenants in the Twin Cities.

The Mapping Prejudice Project, which started at the University of Minnesota, seeks to visualize what communities of color have known for years: white homeowners have been favored in generating land wealth for the past century. The team of researchers hopes to make Minneapolis the first city to map out structural racism by analyzing restrictive deed covenants. Efforts in Minneapolis, in particular, demonstrate the city’s ugly racial disparities, which are some of the largest in the United States.

Anyone can contribute to the research by analyzing covenants. Covenants flourished in the twentieth century as a pervasive part of real estate which restricted people of color from buying or occupying land.

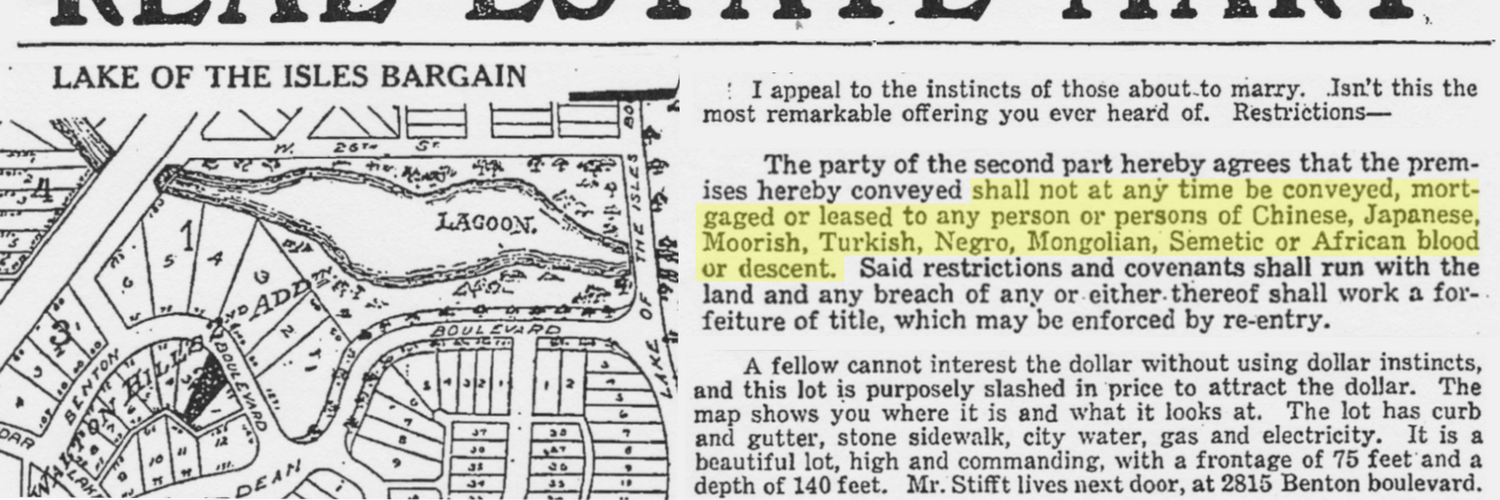

An example of a racial covenant as curated by the Mapping Prejudice Project. The highlighted text indicates the language that was written to keep many real-estate options away from communities of color in Minneapolis.

The legacy of these racial covenants has persisted through the decades. Not only did they separate neighborhoods, they determined those individuals worthy of owning more property. Since many equate wealth through property ownership, the home-owning racial gap lies at the root of the current racial wealth gap. Generational wealth additionally scorches these communities of color; the average white home in the nation has ten times as much wealth as the average black home.

Click here to see the official map from Mapping Prejudice.

When introduced to the project at the Hennepin History Museum exhibit, US History teacher Sushmita Hodges was all ears.

“I’ve been interested in the whole framework about the dominant and absent stories. As a woman of color, it’s important to me to know what’s happening to communities of color. I’ve taught my history classes with an inclusive approach, and the inclusivity is about addressing the silenced voices and addressing those who do not typically get talked about unless they are in relation to the dominant narrative,” Hodges said.

Because of the relevance of the topic, Hodges has encouraged her advisory to contribute to the research. Senior Ethan Dincer jumped at the opportunity to participate. He was inspired by the project’s clear focus on addressing racial segregation, a type of approach often hidden.

The process is simple for Dincer: “There will be questions on the side asking if a racial covenant is present, who was the buyer and seller, which company did the job, block and lot numbers, as well as the date of the transaction. In all, these questions take around 5 minutes to complete, and it is gratifying to know that your answers to these questions will be added to Mapping Prejudice’s online map. Often we shy away from confronting structural racism in our own cities and push it elsewhere to continue bystanding, when it is right here in the Twin Cities.”

Inspired by the work of the Mapping Prejudice researchers, Dincer introduced senior Jazz Ward to the research which connects to their US History Seminar class.

“We had been discussing Andrew Jackson and Indian Removal. We eventually started talking about how Native Americans were forced off their own land, and white settlers began building without a care for their native neighbors. Students often take ‘their land’ for granted. At school, we don’t really discuss where our land came from and who originally was living here prior to colonization. I think Mapping Prejudice could begin to teach students about whose land they’re really living on,” she said.

The project is partnered with Zooniverse, a crowd-volunteering program that allows users to contribute over the Internet. The website contains information and an online tutorial that describes how to identify a racist covenant. From Lake Nokomis to Minnehaha Creek, Minneapolis neighborhoods have a deep history of real estate documents designed to keep anyone other than white out.

Understanding the deeds connected to one’s house sheds light on how even after 1968 when Congress banned these racial housing restrictions, the damage had already been done.

Hodges and Dincer both agree the project works seamlessly into academic historical research.

We’re working with a @UMNGeography class to collect stories about this history. If you’re willing to share, please contact us at: https://t.co/89PllBk7aX pic.twitter.com/89DoF1qSHS

— Mapping Prejudice (@MapPrejudice) October 17, 2018

“I think it’s extremely important for students to understand the community they live in,” Hodges said.

“It is crucial for students to know that Minneapolis was and still is a segregated city and us residents of the area need to acknowledge that. Often we think Minneapolis has been sheltered from racial segregation because we are so far North, but the Mapping Prejudice project shows that, in fact, we are far from desegregation. The project brings a real-world connection to what we learn in US History during [the] 2nd semester on racial segregation, redlining, and gentrification. However, since our US History book is broad, it does not address Minneapolis and its segregationist history with utmost specificity, which makes Mapping Prejudice Project more crucial to understanding our city’s history,” Dincer said.

Hodges plans on spending time on the project in her advisory. Dincer and Ward hope students will reflect upon their neighborhoods and its structural racism.

To get involved, Zooniverse will be hosting a work session to document the discriminatory covenants. The next meeting takes place Oct. 25 at the Weisman Art Museum. Click here to sign up.